Masterclass

Trailers

Monsieur Ibrahim et les Fleurs du Coran

x (x)

x (x)

x (x)

x (x)

x (x)

x (x)

View all trailers

Summary

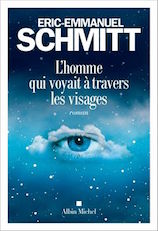

In the bookshops from 1 September 2016

After Night of Fire, Eric-Emmanuel Schmitt continues his exploration of the spiritual mysteries in a disturbing novel that powerfully blends philosophy with suspense.

It all starts with an attack after a church mass. The narrator was there and saw everything… and more besides.

He has the unique ability to penetrate people’s faces and see the microscopic elements (memories, angels or demons) that motivate or haunt them.

Is he crazy? Is he a sage with the power to detect other people’s madness? His investigation into violence and religion leads him to the meeting we all dream of…

Reviews

Le Matin Dimanche (Suisse) - « The best Schmitt to date »

He comes across as a solitary dreamer, but this doctor of Philosophy and, since January, member of the Académie Goncourt, is frequently called to account by the Parisian intelligentsia and right-thinking literati. Such critics consider him saccharine, with his Oscar and the Lady in Pink about a little boy with leukaemia who, in a kind of last gasp, enters into a disarming correspondence with God. Taboo, unpalatable and yet very real, a child’s death is at odds with the divine mystery, which Eric-Emmanuel Schmitt determinedly probes ever more deeply in each new book.

Too often, his “Alternative Hypothesis” gets overlooked, despite winning international acclaim. In that novel published in 2001, he grasped the reins of History and played God to postulate what might have been: Schmitt has Hitler pass the entrance exam to the Vienna fine-art school and thus avoid the frustration and resentment of that early failure.

Last autumn, he put aside fiction to write about himself in a beguiling and mystical account of the revelation he experienced one night when he nearly lost his life in the desert. Night of Fire is a fine and powerful book, a raw diamond that describes the rational mind’s escape towards faith.

In his new novel, The Man Who Could See through Faces, Eric-Emmanuel Schmitt has produced a superlative composite of the different elements of his oeuvre. The subject is disturbing and makes for an addictive, fascinating read. That it appears to be based on current events is intriguing; but that it is so adroitly prophetic is unhinging.

The ability to see the dead.

The narrator is a harassed and exhausted intern at Demain, a local newspaper in Charleroi, Belgium. Half-starved, forced to eat out of dustbins, Augustin lives in a squat, sleeps at the office and is continually upbraided by the paper’s cantankerous editor obsessed only with squalid scoops and shock stories. Augustin is convinced that journalism is just a stepping stone on the road to becoming a writer, a means of earning his keep, even though his current internship is unpaid…

Fortunately, Augustin has a unique gift, a gift that handicaps and isolates him and all but costs him his life. For, Augustin can see the dead. He senses them and he suffers from their presence. Often, he perceives a minute body flitting like a bird above a pedestrian’s shoulder. The apparition is a dead person who wants to stay and could not be buried. Then, one day, he sees a tiny man floating over the jihadist who blows up a local church. When he gives evidence from his hospital bed, he tries to hide his vision and is suspected of lying. But lying about what? Did he know Hocine Badadi? As a fictional character tracing the young man’s trajectory, Eric-Emmanuel Schmitt is more dispensable than the book’s real idea: a drug-inspired interview, which God, called the Great Eye (in all three monotheistic religions) grants Augustin, and in which He calmly explains that the holy book is a source of truth but that down the ages, reading it has been a hazardous enterprise. The best Schmitt to date.

Le Soir (Belgique) - « A must-read »

Eric-Emmanuel Schmitt’s latest novel is an attempt to understand violence committed in the name of God. This is a novel with characters, adventures and reversals, and at the same time, it’s a far-reaching study in philosophy (…).

Notwithstanding a couple of points (…), I recommend everyone to read it. Firstly, it uses fiction to tackle essential issues with the spotlight on the relationship between religion and violence, and it fearlessly challenges God and forces humans to face up to their responsibilities. “I am sick of men”, God says in an interview with Augustin. For men have never thought deeply about God’s literature but have taken it literally and distorted the meaning; they have established dogmas then used violence to defend them. Like Diderot or Pascal before him, Eric-Emmanuel Schmitt makes his readers think, assess and comment. An absolute gift to his readers.

Jean-Claude Vantroyen

Le Figaro - « A novel that overflows with challenges and top-tips »

In Night of Fire, which came out last year, Eric-Emmanuel Schmitt produced a lean account of the spiritual experience he had in the desert as a young man. Since that time, he has been a believer almost in spite of himself. But what and in Whom does he believe? His new book, a fat novel overflowing with challenges and top-tips, is an attempt to answer that question in a thriller loosely based on current events. The story takes place in Charleroi, Belgium. The 24-year-old hero, Augustin, a child of the welfare state, is an intern with a local newspaper. He has the ability to see the spirits of the dead circling around the living. When he witnesses a terrorist attack outside a church, he notices an evil spirit in a djellaba hovering above the terrorist’s shoulder. The police who question him are bound to understand… But Eric-Emmanuel Schmitt’s master stroke is to make himself one of the central characters in the novel. The young hero thus interviews the writer and asks him what he thinks about religion. Then, he goes off to interview God Himself. This is less ludicrous than it sounds and while not always convincing, it is often pertinent and is adroitly handled.

Astrid De Larminat

L'Est Républicain - « A tour de force of style and erudition »

He won’t get the Goncourt: he’s just been elected to the Académie. He doesn’t need success: he’s got that already, with his works translated into over 40 languages and performed in nearly as many foreign theatres. Eric-Emmanuel Schmitt has published “The Man Who Could See through Faces” with Grasset. The novel is a tour de force of style and erudition. Schmitt loves the French town of Nancy: “Enthusiastic readers who are interested in their contemporaries and have enquiring minds. An absolute joy.” And Nancy returns the compliment. In this book about violence and the way God is taken hostage by every religion, Schmitt assigns the main character a quirky encounter. Under the influence of drugs, Augustin interviews God about his literary output. But God ended that career because humans didn’t understand His books. The metaphor is crystal-clear but Eric-Emmanuel Schmitt’s perspective more complex: “You have to be able to read books, starting with the religious texts. It’s reading that makes a book, not the other way round.” For EES, a single book can be read as “a call to crime and violence, or as a stimulus to be kinder, more accepting and more open-minded”. In a society cruelly in want of a religious culture, the latest Schmitt is a shining breviary from an agnostic believer.

Pascal SALCIARINI

Le Progrès - « I needed to bring God back to the courtroom” »

Eric-Emmanuel Schmitt has written a philosophical novel based on current events, The Man Who Could See through Faces. The following interview was conducted in his native city of Lyon, where he was giving a lecture at the Bourse du Travail.

Terrorism, Islamism… Is your latest novel based on current events?

“I’d been wanting to write this novel for years, and after the Paris attacks, I felt the need to write because I wanted to understand. The book is about the origin of violence: I wanted to understand whether it’s attributable to people, to religion, or to God.”

Is it linked to your “revelation” in the desert described in Night of Fire?

“Yes, because when I see people committing atrocities in the name of God, I am doubly shocked. Firstly, as a citizen but then, too, as a believer. The God I believe in doesn’t instil hatred in me: He instils love. He doesn’t lead me to make war but peace. I needed to put God back on trial.”

To what extent is your novel philosophical?

“It’s the genre I’ve adopted, because I think fiction prompts people to take stock. You take the reader beyond his or her spontaneous opinions precisely by inventing characters and stories. Fiction moves people more than non-fiction, and it challenges the major philosophical questions using characters and situations.”

There’s also your fondness for the Enlightenment…

“Yes, I love Voltaire and Diderot’s liberty… Especially when it takes unconventional forms.”

You put yourself in this novel as one of the characters; isn’t that a bit excessive?

“I knew I was going to appear in my book at some point. I tried to avoid two pitfalls: praising myself too much and denigrating myself too much – the two traps of narcissism. But the other thing is, it was easier to talk about myself as a character. It would have been absurd to bring in someone who says exactly what I do but who is somebody else.”

Your novel looks forward to 2060. What is your vision of the future?

“I’m not Cassandra. What I’m suggesting are embryonic solutions. I’m an activist for the idea that you should teach religion and atheism in state schools.

Nicolas Blondeau

Paris Normandie - « A spiritual and philosophical epic - superbly written. »

Augustin, a young intern at a Belgian newspaper, witnesses a terrorist attack in Charleroi. When he is interviewed by the police, he has the adventure of his life. For, he has the unique ability to see what others cannot see, namely, living creatures hovering around men and women. Are they angels or devils, vanished or deceased people? As a result of this ability, he encounters incredible personalities and interviews the least probable. Loosely basing his novel on the violence and fanaticism of recent events, EES probes the motivation for terrorism and radicalisation. After Night of Fire, he continues his spiritual quest and his exploration of God and religion. Strikingly in this book, the author introduces himself as one of the characters, assigning himself a central role among the major figures who have been his inspiration. We loved this spiritual and philosophical epic tale, whimsical but superbly written.

I.C.-L.B.