Masterclass

Trailers

Monsieur Ibrahim et les Fleurs du Coran

x (x)

x (x)

x (x)

x (x)

x (x)

x (x)

View all trailers

Summary

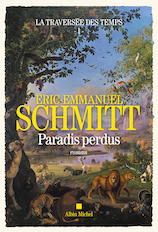

In Traversée des temps (Crossing Time), Eric-Emmanuel Schmitt has set himself a momentous challenge: to tell the history of humanity in the form of a novel. Scroll through the centuries, embrace epochs, feel the shocks: Yuval Noah Harari meets Alexandre Dumas! Schmitt has been developing this project for over thirty years. Bringing together scientific, medical, religious and philosophical knowledge and creating strong, tender and very real characters, he propels readers from one world to the next, from Prehistory to our own time and from evolutions to revolutions, while the past illuminates the present.

Paradise Lost is the first leg of this unique journey with Noam as its narrator-hero. Born 8,000 years ago in a lakeside village deep in a paradisal natural world, he confronts the tragedies of his clan the day he meets Noura, a capricious and fascinating woman who reveals him to himself. He is faced with a famous catastrophe: the Flood. Not only does the Flood place Noam-Noah on the stage of History, it determines his whole life. Will he be the only man to traverse the centuries ?

Reviews

Le Monde - « The Bible is a novel that is constantly being written »

The history of humanity in the form of a novel: that’s the challenge the author of La Traversée des temps (Albin Michel, 576p, 22.90 euros) (Crossing Time) has set himself. In it, he revisits humanity’s founding texts in eight volumes.

Eric-Emmanuel Schmitt has a fondness for short formats and short stories. This time, in Crossing Time, he has produced a novel on a totally different scale, or rather, he has produced “novels”, because the series consists of eight volumes and clocks up a total of nearly 5,000 pages. That’s what it took him to face the challenge he set himself at the age of 25: to tell the history of humanity in the form of a novel.

Taking as his basis the founding texts of our culture, starting with the Bible and the Epic of Gilgamesh – which he revisits and updates --, Eric-Emmanuel Schmitt explores the past to illuminate the present. Paradis perdus (Paradise Lost) is the first in the series. Using the Flood as the backdrop, he brings on stage Noam, a hero who becomes immortal and who will accompany the reader throughout this ambitious journey down the ages.

What persuaded you to take on a project of this magnitude?

Eric-Emmanuel Schmitt: Painters say that the subject commands, they say it calls for a specific size of canvas. It’s the same in literature. I’m more of a scribe than a creator: I obey the subject that comes to me. This book came to me in a flash just after I’d completed my PhD in Philosophy at the Ecole Normale Supérieure. I had an idea for a mammoth book that would tell the story of someone immortal across the centuries, describe the events that founded humanity and show us how we came to be what we are. But at 25, I didn’t feel able to take on the project. So, I procrastinated for ages because I was afraid to launch in. The project turned into a plan, however.

What was your methodology in planning the series?

I spent years gathering sources. Everything I’d written was both an end in itself and a preparation that would enable me to develop my painter’s palette. At the narrative level, a massive design process was necessary before I could start. I built an architecture for the series to structure the entire plot. Once the tree of possibilities was in place, I began to write.

The influence of The Epic of Gilgamesh is clear in both the theme of immortality and the character of Noura, who’s not unlike the cheerful prostitute of the Mesopotamian text. Is it one of your bedside books?

Absolutely! The founding books of civilisations are tales that try to organise meaning and explain how we got here. In that sense, Gilgamesh and the Bible have tremendous interest for me. What I like doing, is suggesting a version other than the history that has come down to us. I want to show how people are linked by the common fictions they believe in.

What is your relationship with the Bible, given that Paradise Lost borrows from the episode of the Flood?

For me, the Bible is a novel that is constantly being written, a novel that is continued by critical commentary and which, even now, is perpetuated by scientific commentary because of the way scientific commentary questions its historical basis. I’m impressed by the capacity of the Bible to go on generating meaning and fiction, today just as it did yesterday. I’m inserting my own moment into this infinite novel.

I’m fascinated by the problems associated with the historical facts of the Bible. You can see that the Bible is a narrative in the making, that it has several layers of text, for example, in Genesis, and that people want to say different things in the text according to the era. I think the Bible is an education not just of people but also of God.

Progressively, it reveals the figure of a god who matches up to God. In the course of the narrative, you see how the idea of God, initially perceived as angry or vindictive, is refined and defined. I actually see the story of Abraham as an education of God and not of the patriarch. When Yarweh asks Abraham to sacrifice his son, Abraham seems to be telling Him, “If you are God, prove that you are equal to God and stop me!”

You say you had a mystical experience in the desert, which you related in La Nuit de feu (Albin Michel, 2015) (Night of Fire). Did that experience turn the atheist that you were into a believer?

These days, I prefer to categorise myself as a Christian. Reading the Bible certainly added something to the faith I received in the desert, which wasn’t linked to any religion. I came from an atheist background but at that moment, I had an experience of the Absolute, of God.

But because I became a believer in that way, virtually out of context – the desert was a pretty basic kind of context –, I found my way into many religions through my reading. All mystics are my brothers and sisters, whether they are Buddhists, Muslims, Jews or Christians: they describe the same chaos and, in fact, they don’t describe it well because no discourse can put words to the ineffable.

All the same, my belief took shape by way of the New Testament, which was defining because it proclaims the supremacy of love. Hegel said love is “unwavering”, that it can’t be the fruit of reason. It’s an affirmation, a kind of madness, an impulse.

To replace suspicion, fear and self-interest with love, the way the Evangelists do, was unheard of. For that reason, I call myself a Christian while at the same time assuming the heritage of Western philosophy, of course.

Are you practising?

I’m very happy to share my belief with other people, but I don’t need to be with other people to experience that belief. So, I’m not someone who attends ceremonies or rites. My belief is nourished by silence, meditation, prayer, an experience of the world and even the internal drive I feel inside me.

Did your examination of the historical truth of the Bible and the other religious traditions in order to write Crossing Time make you question your spiritual convictions?

Writing the book didn’t alter my belief, it contextualised it. I agree that, when you face the archaeology of your own beliefs, you can feel unhinged by the realisation that there are contingent aspects in the Bible, aspects that might have not been. If, in writing the story, I might sometimes have felt my belief faltering, I don’t feel like that now.

Like Bergson, I think that all the religions have the same heart: a heart of fire, a mystical heart. Religion is a way of putting words to the ineffable; religions are ritualisations, ways of behaving, institutions whose aim is to organise words and actions. Eventually, people move so far from the mystical heart that the whole thing ends up being cold, frozen even. In many cases, the important religious person is the one who gets close to the centre, who brings the fire back to the institution.

You write, “Only those who love and respect the laws of nature will survive calamities”. What made you place your book in the context of the ecological crisis we’re living through?

I see it as peculiar to the early 21st century that humanity has become aware that it is an excrescence. Humankind has become “master and possessor of nature” to the point of destroying it and possibly of destroying itself. Having revelled drunkenly in their mastery for centuries, contemporary human beings have got a hangover from the realisation that their super-domination is a dead-end.

The book is called Paradise Lost because there’s something lost in the life Noam lived in the Neolithic: animism, the idea that man is only a guest among nature’s guests with no special or superior status. He’s just a living being among other living beings. And living beings are not only humans and animals but also plants, stones, the wind and all the elements of the natural world. In animism, humans aren’t especially privileged with a mind: there are minds everywhere – the world is both completely material and completely spiritual.

But man has progressively appropriated the privilege of the mind until he thinks, like Heidegger, that he is the only “shepherd of Being”. Those Prehistoric men and women we look down on had a kind of wisdom and a way of being in the world that might be an inspiration for us. Because there’s happiness, exhilaration and even consolation in existing as a natural being among natural beings with no special status.

Immortality is often seen as the Holy Grail, but you say that the characteristic affecting your hero, Noam, is “a curse”. How do you perceive transhumanism, which endeavours to push back boundaries?

Science produces scientism and humanism has produced its opposite with transhumanism. It’s what you get when a process becomes fundamentalism and an autocratic ideology. Whereas humanism is an awareness of human vulnerability and the resulting morality of responsibility – with the idea that our mortality is the basis of our existence –, transhumanism claims to escape the human condition.

Apart from the fact that that utopia will never come to pass, it’s insane and a vector of war between rich and poor, between those who can access the technologies and those who can’t. So, the ideology produces the opposite of what it promised.

If life is endless, it ceases to have any meaning. “God or nature”, in the words of Spinoza, intended the species to be perennial and individuals to die. We receive life and pass it on, but it doesn’t belong to us: it is the property of the species. The idea that individuals might be more than the species is an outrageous existential and metaphysical rupture, especially because immortality isn’t the answer to everything. We would then be immortally ignorant.

While you’ve been working on the series, have some periods of history seemed more desirable than others?

No. I love the age we live in passionately, including with its faults. I find interest and things to nourish me in every age, but I never fall prey to nostalgia. You can wonder about it, of course, since the issue is “Paradise lost” but I think that, at the end of the day, no Paradise is really lost.

“No one exactly lives in his era”, Noam says in an aside. Intermittently, we all live through our dreams and aspirations in another time than the one we belong to. They’re the spaces provided by poetry and the imagination.

You said that working on this might sometimes have weakened your religious beliefs. Did it also sometimes weaken your faith in humanity?

Yes, absolutely! I get the feeling that, left to themselves, human beings don’t learn. Not that teaching history is pointless (on the contrary, I believe in it profoundly). But I realised that, although humanity sometimes does marvellous things, it’s usually for the wrong reasons.

In his essay, Idea for a Universal History with a Cosmopolitan Purpose, Kant explains that humanity never wants good as such, it wants what is least bad. So, he foresaw that there would one day be a society of nations, because peoples would tire of war and want regulatory authorities. So, evil was what led to the advancement of good.

I am metaphysically optimistic but pessimistic when I look at society. I’m metaphysically optimistic because life is a sublime gift, but it’s what humans do with that gift that makes me very pessimistic. We don’t live up to the gift we’ve been given. I don’t myself feel I live up to the gift of being alive and being a human among humans.

“I am metaphysically optimistic but pessimistic when I look at society.” Is writing no consolation for that feeling?

Writing is a kind of self-care. It’s a time of retreat from immediate demands, from social life and from the norm, it’s a space where you can rebuild yourself and remember who you are – just like the space of dreaming at night. Michel Jouvet (1925-2017), a neurobiologist, observed that dreams re- individualise us, whereas society atomises us, pulverises us with its dictates. The time devoted to writing is also a time of re-individualisation, of recovery of the self. Writing is an existential project.

Virginie Larousse

Livre Hebo - « I feel as though I was born nostalgic! »

Marrying the major metaphysical questions with fictional expression, Eric-Emmanuel Schmitt has produced an eight-volume epic on humankind, La Traversée des temps (Crossing Time). Volume 1, Paradis perdus (Paradise Lost) launches the series of novels.

Where did such an ambitious idea for the history of humanity come from?

Eric-Emmanuel Schmitt: Like a bolt from the blue that struck me when I was 25! I was just starting out as an academic in Besançon. I’d read nothing but the literature of ideas for my Philosophy PhD, and I was wallowing in an orgy of novels, rediscovering the joy of reading simply for my own pleasure. I was still imbued with the spirit of the encyclopédistes, notably Diderot who’d been the subject of my thesis and who himself is a borderline author between philosophy and literature, and the idea came to me of a man endowed with a characteristic most people would envy: he would never die. My hero would travel through time and show how today’s humanity was constituted. An anthill, a termite’s nest, a beehive... it hasn’t budged for thousands of years. The unique feature of human society is that it is not natural and it changes. Humanity itself is probably man’s creation. I wanted to explore the history of humanity, but I didn’t want to end up with an encyclopaedia. Instead, I wanted to write novels with all the force of fiction so that the story wouldn’t just be a skeleton but would have flesh.

Why did you give it a Biblical beginning with a protagonist called Noam, like Noah, and the episode of the Flood?

The Bible is a source of infinite inspiration. I’ll continue to talk about it throughout the series – not the Bible as a reference text but as one of the stories of History. In terms of the Flood, the original cataclysm diverted the course of mythical tales but also of scientific research, serious archaeology and every kind of exegesis. The story of the Flood continues in other episodes – I’ll show how, especially with the Mesopotamians and Gilgamesh. The Bible is a story, but it isn’t the only one: the story is constantly being rewritten, and the Bible itself is constantly being rewritten, in every age, through our interpretations and discoveries. References to it interest me when they relate to other stories.

Let’s get back to Noam/Noah. Why did you choose this ancestral figure rather than another Old Testament patriarch, or even the Greek Titan, Prometheus?

This first volume kind of sets the scene with a Neolithic backdrop. It’s the last time nature got the upper hand; after that, humans dominate. Noah finds himself at that pivotal point. Today, we live in a totally “hominised” natural world that’s been unbalanced by human activity – what’s called the Anthropocene. Noah wants to save the old world he comes from. He is in an environment that’s stronger than him where God, or Nature if you want to follow Spinoza, is everywhere and takes charge of lives. I saw Noah as having a formative role in History which, for me, starts after the Flood. Societies before the Flood were in a pre-larval state, because Prehistory was more about clans.

Do you mean that everything was “religion” in the sense of the connection between things, that everything was linked?

Yes, viewed like that, the world consists of a network of meaning, because man is not the keeper of meaning. According to monotheism, he received the Word (meaning via speech) from God and he is the only one to be able to give meaning to things, because animals don’t have the gift of speech. In animism, by contrast, spirituality is everywhere: everything that makes up the world both receives and gives meaning.

If this book and the next seven are supposed to follow the course of History, you’re playing with temporal distortions or uchronia, aren’t you, the way you did in La Part de l’autre (The Alternative Hypothesis) where you imagined that Hitler had embraced the career of a painter?

I liked the idea of defrosting Noam in the contemporary age. It was essential to use the past to shed light on the present and vice versa. When you look at the past, you see it through a window cut into the wall of the present. The past appears to us through contemporary preoccupations. We look to it for how the present can tap into it or contrast with it in order to understand it. It’s always the present with its modern anxieties, always present-day society with its contemporary issues, that digs into the past looking for roots or ruptures. In Paradis perdus (Paradise Lost), we witness a tipping point: the era Noam comes from is contrasted with our own to reveal a deep rift: we go from a man who is nature’s guest, a guest among guests without superior status, to an outstanding hero who completely subjugates nature to the point of destroying Her.

From the narrative point of view, that allows you to use a fair bit of irony...

Noam has the ability to hibernate, to spend time in a long sleep that distances him. In caves, in damp spaces like bellies, like a return to the womb, he escapes from other men and is reborn. Even when he’s wounded or actually destroyed, he can recover in that cavern. Every time he’s reborn, he will emerge endowed with an enormous baggage of previous periods but also with perpetually renewed innocence, like the Persians in Montesquieu.

The French title “Paradis perdus” is plural: why is that?

From the outset, I wanted Paradise to have multiple meanings. Paradise is firstly a historical time when human beings had not yet taken control of nature, when they were evolving equally among living beings. Next, Paradise is the time of poetic ecstasy with nature and also amorous ecstasy or mystical ecstasy. So, Paradise is in the plural, and they’re all lost because none of them exists any more. It’s something that’s always struck me, the impression of being nostalgic. In psychoanalytic Jungian terms, the lake is the mother – sleeping, soothing water from which we’ve been violently cast out.

In the beginning was the Flood. And also desire... Your Crossing Time is also a love story, isn’t it?

I wanted to tell a love story spread across centuries involving two characters, Noam and Noura, who think the same but never at the same time. They aren’t synchronised. You can be immortal with a completely different relationship to time. Noura doesn’t react like Noam because her body is a woman’s body, a body that can’t escape time and the rhythm of cycles; hers is a body that is not an end in itself because it is designed to give life. Noura might have received immortality but she develops a kind of frustration and impatience and sometimes an inability to enjoy happiness, a hatred of herself. She is such a complex character that I can deal with her for thousands of pages via Noam, whose fascination with her allowed me to itemise the thousand faces of love.

But you could have told an epic about humankind by writing about successive generations. Why did you use an immortal narrator?

It’s never explicitly put like that. From book to book, there are multiple interpretations, but immortality will remain a gift, a mystery which struck the characters like lightning. Maybe I wrote this story about immortals to domesticate my own mortality. Maybe it was to tell myself, and readers, too: you know, it’s better to be mortal, better to shoulder the transitoriness bestowed on us only so we can inhabit the human condition. The further I get with the series, the more I realise that immortality is an absolute torment: Noura and another darker character called Derek are the

proof. Not only does perpetuity generate loneliness, but immortality produces non-meaning. Mortality includes us in the story of life which will go on without us. This life we’ve received only has meaning because we bequeath it in our turn. I don’t mean that just in the biological sense: the children of an artist are her compositions. The important thing is transmission.

Sean J. Rose

Le Figaro - « A superb novel »

WHEN Milton wrote his famous poem “Paradise Lost”, he was blind. He wrote, corrected and re- read his masterpiece from memory. Chateaubriand, who translated the work into French, was quick to praise such a “monumental effort of memory”, but he had even higher praise for Milton’s incantatory and divine writing. The genius of poetry -- from the Greek “poiesis” meaning “creation” – was certainly essential to tell the genesis of the world four centuries after the English epic poem.

None of that epic quality has been lost in Eric-Emmanuel Schmitt’s Paradis perdus (Paradise Lost), a superb novel, the first of eight in a cosmological project born some thirty years ago.

As you can imagine given such a Titanic challenge, time is central to the series. For Schmitt as for Milton, the history of the world and the memory of the world are one and the same. By going back to the origins of a life – not “the origins of life” because this isn’t about Adam and Even –, Schmitt can rewrite what we call common myths and tales. Rather than a pagan, pantheist Bible dotted with scientific, religious and philosophical footnotes, this collection of novels turns out to be a proper adventure story.

A hellish present

It all starts with a shiver. A 25-year-old man is waking up. As he gets up, he hits his head on the walls of a cave. Are we in Prehistory? No, a cigarette lighter is pulled out. Moments later, the stranger plunges into the crowds of Beirut. Who is he? For now, all we know is that he is called Noam and that he is thinking of “Her”. Who is she? We don’t know that either.

The mystery continues as page follows page, while young activists take to the streets protesting against climate change. “During his hibernation, humanity had carelessly generated its extinction.” Noam senses that it won’t be long before the world ceases to exist. Is this a “collapsology”? Not yet. But, as fire engulfs the landscape, Noam sits down to write his story. Playing God in his text, Schmitt leaves nothing to chance. A setting nothing short of “apocalyptic” (from the Greek “revelation of God”) is required for Noam to unveil the story of the Creation. Thus begins the first part, written down from its creator’s memory. The man writing is 8,000 years’ old. “When writing was invented, I was already four centuries’ old.” Without expanding on his childhood – he is the son of the village chieftain, Pannoam, who was given a wife at the age of 13 –, he soon gets to the book’s subject: “She”, which is to say, Noura, the woman who brought him into conflict with his father for the first time in his life.

From here on, Schmitt constructs his tragic – and Biblical – plot. Love generates freedom and with it, revolt. Should he give in? In the course of his tale, another world, shaped by beliefs, emerges, a world where people live with respect for Nature and the Spirits that comprise it. But all that will change with the Flood. Noam/Noah recalls those bygone days, his sorrows and his regrets. Dante’s words come to mind: “There is no greater sorrow than to recall in misery the time when we were happy.” Since the Stone Age, Noam has lived in a hellish present. What has happened to him? Is he the only one to be living forever? Bring on the sequel!

Alice Develey

Le Matin (Suisse) - « Enthralling »

A man wakes up naked in a cave. He does not know who or where he is, nor what century it is. Once outside, he realises that he has fetched up in Beirut in the 2010s and is fascinated to discover mobile phones, climate crises, TV and the internet. His name is Noam, he is immortal and he is a healer, he has lived in several civilisations over the years and is preparing to tell us his story – a very long story beginning 8,000 years ago when Hunters fought Gatherers at the end of the Neolithic, and ending after 5,000 pages or eight volumes of more than 500 pages each, in the 19th century of Industrial Revolutions.

Along the way, Noam will have told us about Babel and the civilisation of Mesopotamia in La Porte du ciel (Heaven’s Gate), then about Egypt at the time of the Pharaohs, Ancient Greece, Rome and the birth of Christianity, Medieval Europe and Joan of Arc, the Renaissance and the discovery of the Americas. In every age, he finds his feminine alter ego in Noura, a beautiful, unpredictable and fascinating woman with whom he fell irreparably in love as the son of the village chief, beside a lake that became an ocean.

Ten thousand years of history in a novel

Eric-Emmanuel Schmitt has been incubating his saga for over thirty years, amassing a vast knowledge of history, science, religion and medicine down the ages, rereading the Bible and the Epic of Gilgamesh and building the architecture of his series a thousand times, driven by a single grand ambition: to tell the history of humanity in the form of a novel.

What might sound presumptuous – does the Eric-Emmanuel Schmitt we know and love really hold the truth to ten thousand years of the history of the world? – or arrogant – even Balzac and Zola in a hundred books of the Human Comedy and twenty books of the Rougon-Macquart series were only claiming to tell the society of the 19th century (Balzac) and the natural and social history of a family under the Second Empire (Zola) – or outmoded: do we really need a novelist to understand History? – turns out to be a surprisingly pleasant read.

Turning the pages of Paradis perdus (Paradise Lost), the first volume of La Traversée des temps (Crossing Time) is like being welcomed on board the Orient Express, with personal service and chilled Champagne, for a long, comfortable journey. On board this saga, everything is done to make us feel at ease: the keen, experienced pen of a successful novelist and playwright, author of The Visitor, Oscar and the Lady in Pink or The Bible according to Pilate; his obvious enthusiasm for telling us this story; engaging heroes; the irresistible attraction of fictional machines that turn back time, and the gratifying impression that we are learning about everything while having fun.

A celebration of humanity

Schmitt’s method reaches its apogee here: he is a master at representing the grand philosophical, social and psychological questions with key, flesh-and-blood characters. Our relationship with nature; the complexity of passionate and family ties; what progress brings human beings and what it takes from them; the suppression of individuals by automation; the roots of racism; the infancy of trade; relations with the numinous and the gods, and the perception of our own emotions: these questions are personified in the first novel by Noam, ancestor of everyman, his father Pannoam, the giant Barak, his wife Mina, his son Cham, and Noura his unattainable love. This celebration of humanity has been the hallmark of the Belgium-based writer since his earliest books in the 1990s and it has been central to the unique rapport he has with his readership.

As the sage Tibor says to Noam – and maybe Eric-Emmanual Schmitt is confiding life’s great secret to us – “All living beings are survivors, Noam. The living survived birth, childhood illnesses, famines, storms, conflict, the cold, pain, separation, sorrow and fatigue. The living had the strength to progress.”

Isabelle Falconnier

L'Orient - Le Jour (Liban) - « A superbly crafted human adventure told with outstanding talent.” »

Novel, non-fiction, coming-of-age story, or fantasy tale? French author, Eric-Emmanuel Schmitt, has rolled several genres into one in this literary phenomenon published by Antoine at a special Lebanon price.

Paradise Lost (563 pages, Antoine), a new novel with a Miltonian title by Eric-Emmanuel Schmitt, is the first in a series of eight volumes brought together under the title La Traversée des Temps (Crossing Time) to appear over the coming years. Thanks to the publishing house, Antoine, it is available at a “special Lebanon price” (cf, the latest Amin Maalouf, Nos frères inattendus – Our Unexpected Brothers). Lebanese readers, labouring under the dictatorship of impoverishment and the spectacular fall of national currency, will not be excluded from culture. Put another way, hyperinflation will not have the last word where the word is king. A real door-stopper that defies categorisation, this ambitious literary work-in-progress encompasses literature, philosophy, history and the fluctuations of the human heart. For over 30 years, the prolific author, playwright, director and actor, with French and Belgian citizenship, has fostered a momentous project in his head and in his heart: to tell the history of humanity in purely fictional form, to enter history by way of stories.

For him, humanity as it is today began 8,000 years ago in the Cave of Jeïta 18km outside Beirut, now a failing and disintegrating city. But the author of Oscar and the Lady in Pink doesn’t see it that way, notwithstanding the darts he casts now and then at its dodgy electrics, flaky supplies and the hazardous pollution emitted by forests of power units.

In a lakeside settlement blossoming with stalagmites and stalactites, the immortal Noam comes to life aged 25 after a long sleep. The Cave of Jeïta appears as though seen through the lashes of his half-open eyes.

After the first shock of contact with the earth (he hits his head on the cave walls), Noam, the narrator, a fictional character and witness of the past and of the present, bounds out of an Edenic landscape of abundant vegetation, oceans, rivers, mountains and valleys, out into the wide world. His aim: to find the woman he carries in his heart and in his senses. Cue for a dizzying carrousel of excitement, wisdom, knowledge, sensuality, otherness and discovery that make for an enthralling quest. A natural catastrophe will turn his life upside down: the Flood. Noam-Noah becomes immortal and enters the History of Humanity. He narrates how he travels through time. Will he traverse the centuries alone?

Schmitt is like an indomitable magician and the novels in his Paradise Lost are like the elusive tapestry of the Thousand and One Nights, which cannot be contained in a casket or told in a single night. So, the reader is catapulted by this tousled narrative into a universal history that bestows so much on the rich and powerful (an odd observation in this first volume) and where Noura, the beautiful heroine and chosen heart-throb of the protagonist (who speaks over 20 languages!), appears in gorgeous finery, lingeringly described down to her sumptuous dresses and shoes.

Emphasis on the daughters of Eve

Good intentions abound among a cast of characters who are admirably portrayed, especially the women. Indeed, you’d say that the daughters of Eve, inspirational life-givers, take pride of place in this life-affirming work. There’s the intriguing and beguiling Noura then a delicious cast of female characters – male, too, of course. They are characters who are touching, spirited and funny with foreign-sounding names: Tibor, Ponnoam, Mina, Barak, Tia. There’s also Elena, an amazing mother --

how could it be otherwise, given Schmitt’s devotion to his own mother and the tributes he has paid her in more than one book and on several occasions?

The tribulations of this Neolithic era are uncontrollable if not entirely true to life. With bewildering agility, the novel cunningly conflates epochs, zooming in on the mobile phones, high-rise blocks and hectic pace of contemporary civilisation.

From love to jealously via fatherhood, life in all its complexity and paradoxes unfolds in the heart of a lush, virginal natural world where the lure of the verdant jungle is nevertheless deceptive. For the author interpolates his own reflections on wind turbines, the origins of aspirin and dental hygiene with perspicacity (im)pertinence and topicality!

An array of unhinging and arresting subjects in this mix of cultures, knowledge, science and erudition add to the poetry of pure, majestic, sovereign nature, which comforts those who listen and is friend to those who respect it. For nature provides nourishment and perennial wisdom.

Schmitt’s Paradise Lost shuttles seamlessly between Prehistory and modernity with scholarly and subtle interaction. And therein lies the originality that characterises this ground-breaking work. Its beauty, fluidity, precision and masterful use of language are incomparable and never for a moment flag or fail.

From its joyful opening, the successive volumes of this magisterial and ambitious work-in-progress should be welcomed with deference, delectation and pleasure, not least so that we can revisit a timeless fictional series offering an encyclopaedic breadth of knowledge, a plethora of lessons for life and, above all, an exhilarating account of the human trajectory.

Seizing the reader and propelling her beyond the familiar purr of fiction, this is a universal history that breaks the codes of conventional narrative, stirs the imagination and feeds the mind through a myriad of voices and layering of civilisations. Combining philosophy with passion and an endless source of knowledge, Paradise Lost is a superbly crafted human adventure told with unbounded talent.

To say, “we look forward to the sequel” pales into euphemism!

Edgar Davidian

Le Pèlerin - « An author explores the past to better illuminate the present. »

With La Traversée des temps, Eric-Emmanuel Schmitt has embarked on his epic cycle of novels. Its challenge? To tell the history of humanity through the peregrinations of an immortal hero. We meet an author exploring the past the better to illuminate the present.

At a time when we’re undermined by Covid-19, you’re dramatising a character who’s immortal. Lucky him, not worrying about catching the virus!

Are you quite sure of that? From what I see in Noam, my character, it’s more of a poison, a curse. The meaning of life is not to stop its course but to pass it on. Watching those we love grow old and die, seeing our own children perish, involves terrible suffering. And also, Noam’s longevity unhinges people and poisons his relations with them. The unique feature that he has condemns him to radical solitude.

Your hero makes a strength out of that constraint.

Noam’s difference leads him to question himself and to set forth. Readers of the Pèlerin magazine will know that spiritual drive, that internal quest. During his travels across ages and places, Noam will accumulate knowledge and become a healer. Condemned to immortality, he will search for the secret of life for other people.

Why did you create this immortal hero born eight thousand years ago?

To tell the history of humanity through his eyes. Noam goes from hunter-gather to sedentary society. He sees the birth of writing, economics, the development of religions and political systems, scientific inventions and the arts and the rise and fall of civilisations. He is like Montesquieu’s Persian travellers who cast a fresh eye on France when they visited in the 18th century.

Noam-Noah – a play on first names – is confronted by a Biblical catastrophe: the Flood.

And he escapes, saving his kith and kin. The Flood is God’s last work of wrath in the collective imagination as conveyed by the Bible. I’m not denying the other plagues, still less the one we’re going through, but neither the Bible nor the ten Plagues of Egypt have the same symbolic power of the Flood. People have come together around that story.

A founding story perpetually retold...

It’s a story that is endlessly rewritten by theologians and scientists. The last were discovered in 1993 in the Black Sea, ancient fossils of plants and freshwater creatures. It generated an interesting hypothesis: at the end of the Ice Age, the melting ice raised sea levels, created the Bosporus dam and drowning a vast lake – where Noam lived – and the surrounding plains. The Flood was not universal, it was local. In the absence of writing, the cataclysm came down to us distorted and amplified and expressed as a fable.

To get back to Noam: he witnesses specialisation. Why does that undermine people?

Noam is self-sufficient – he can feed, clothe and house himself and he can look after himself. Then he discovers sedentary and complex communities where labour is split up and knowledge is piecemeal, where the person who looks after farm animals no longer knows how to hunt or weave. The specific competences of each individual grow to the

detriment of individual autonomy. People start to depend on one another and are condemned to collective life.

Loss of self-sufficiency, economic dependency... The drift your hero highlights, eight thousand years ago, strangely heralds the crisis we’re going through. Can the past shed light on the present?

I think so. From the end of Prehistory, Noam points out the danger of organised dependency, the risks of altering the landscape, of burning, dividing up Nature and of transforming species. He watches as people go from the status of guest in the world to one of domination. Many problems we have now come from that will for power. We think we’re above Nature and we destroy the paradise by wanting to domesticate it. To survive cataclysms, we’ve got to respect life.

You ended the manuscript of Paradise Lost just before the first lockdown and the end of “the world before”. Do artists have second sight?

Artists are sounding boards that vibrate to the noise of the world. A writer can sense, in spite of herself, the fears and uncertainties of her age and she produces something that transcends her. An artist isn’t a creator, she’s an interpreter: a great ear that organises the sounds she hears. Yes, lockdown began when I was writing the last line of Paradise Lost. Don’t ask me why I began the theme of the Flood when the pandemic was submerging us: I was as amazed as anyone.

This tale of time travel is a colossal project. When did it come to you?

I’ve been thinking about this saga since I was 25. I was finishing my thesis on Diderot and I was fascinated by his encyclopaedic knowledge. I was a lecturer in Philosophy at the Besançon University, a city I could hardly point to on the map! And while I was in the train that was taking me to Doubs, a mysterious train like the one Harry Potter takes to travel to Hogwarts, I imagined an immortal healer who would travel through time, a man who would tell and explain the history of all people. But I was paralysed by the magnitude of the endeavour. I first needed to cement what I’d learned, I needed my knowledge to be sifted by life. From an artistic point of view, I gave myself the means to do that: each of my books was an end in itself, of course, but they were all also a way of broadening my palette and trying out my project. My Cycle de l’Invisible is an exploration of the religions. The Bible According to Pilate and The Alternative Hypothesis... My whole literary trajectory has led to this great series about the history of humanity.

This project of maturity brings together your story-telling and philosophical talents with your passion for teaching, because you make readers review fundamental questions.

I wanted to share my philosophical, scientific and religious knowledge with my readers. My authorial notes are important in this series: they explain Noam’s peregrinations and provide keys to the periods he crosses, offering chronological signposts and ways of looking at things. I checked them and rewrote and sculpted them hundreds of times. They’re painstakingly researched but they’re also a source of humour and of complicity with readers who become my fellow travellers, learning and questioning alongside me across the ages.

You like talking to the masses and making knowledge accessible to everyone. Would you define yourself as a humanist author?

A humanist author in the sense that I make differences my own. I try to bring people close to anyone who’s not like them. My novels are imbued with an equal passion for

humanity and for Nature, which are indissociable in my view. We’re all bothered by the same doubts and questions. We’re all responsible for life.

Questions which, in your books, lead to questions about God and the religions.

Because the religions are humanising. They don’t all lead to divinity, but they all lead to humankind, that biped without wings who has to transcend the egoism of its body and shake off its primary needs to access altruism. Being human is not a given, it’s a project, and the religions design a model to achieve it. The most romantic of all religions is Christianity which places love at the centre: love is an irrational feeling that can change the face of the world. Noam is born well before the arrival of religions but he is revealed by love. Love for his mother to whom he owes his life, love for Noura to whom he owes his identity. Love is the catalyst of his development.

When is Book 2 coming out and where are you taking us in that next book?

Next September and Noam will take us to Babel to the heart of Mesopotamian civilisation.

We can’t wait to read the sequel!

You’ve got to give me time to write it first! In the meantime, encourage your readers to read, even if it’s just the superb Goncourt winner our jury is so proud of [Eric-Emmanuel Schmitt sits on the jury]. Reading is an antidote to the difficulties we’re experiencing. If you feel you can’t see the future, literature will offer you a vital space to rebuild yourself. Literature offers meaning and orders the world and at the same time, it isn’t didactic. A book opens doors and perspectives. Because, however engaging a story is, you never read without thinking of something else, without rebuilding yourself and touching base. Reading allows you to renew yourself and to stock up on dreams and strength so you can get back up.

Catherine Lalanne

France Culture - « A talented story-teller broaches a grand literary project »

“Yuval Noah Harari meets Alexandre Dumas...” With this first volume, the supremely talented story- teller broaches a grand literary project: to tell the history of humanity in a novel. Eric-Emmanuel Schmitt begins his epic project with Noam as its narrator-hero.

Albin Michel published Schmitt’s La Traversée des temps – Paradis perdus (volume 1) (Crossing Time – Paradise Lost (volume 1)) in February 2021. This is the first volume in his fictional and epic history of humanity, a massive literary undertaking, matured over a period of more than thirty years, to tell 8,000 years of history in 5,000 pages.

Schmitt’s unique telling of human history traces the adventures of Noam, a character reborn in every era. When he arrives in the contemporary world in Beirut, he experiences climate catastrophe and the sense that the world is about to end. Cue for a description of one of his previous lives, when a vast flood marked the end of an era and renewal. He decides to write down his histories in The History of Humanity.

Noam acts as a kind of witness and is sometimes an important player on the stage of humanity. He offers a bird’s eye view of our history, noting the differences that characterise each era but also humanity’s steadfastness. He observes our present with detachment and wisdom: how often has he heard talk of the end of the world in centuries gone by!

Olivia Gesbert

Psychologies - « I’m an optimist out of pessimism »

In his new novel, the Franco-Belgian writer and philosopher has embarked on a series of eight volumes devoted to the history of humanity. Here is a man full of appetites and energy.

Psychologies: How did this colossal project come about?

EES: I was 25. I’d just finished at the Ecole Normale Supérieure and got my PhD in Philosophy, and I’d finally started reading again – when you study Philosophy, you don’t have time to read anything other than philosophy! I was deep in Marguerite Yourcenar, especially her Memoirs of Hadrian, and also Mika Waltari. I was fascinated by the power of a novel to capture intimate History and provide access to epochs other than our own. It was then that I had the idea of a healer possessed of immortality who travelled through time. The project scared me, but it turned into a plan of action. It gave me an appointment with myself, according to the dynamical principle that you have to surpass yourself to gain knowledge. The challenge stayed with me for decades, and in the meantime, I produced other work that helped me build up my writer’s palette. I needed to increase my lung capacity.

Was this “total world” about getting to the essence of human nature?

EES: Yes, it’s a novel by both a historian and a philosopher seeking variables and constants. On the one hand, I’m doing philosophy and anthropology, trying to update what, in the human condition, always leads to the same needs, difficulties and questions, whether in the Neolithic or today; on the other hand, I identify the transformations that made us what we are: the events and the technological, climatic and sociological changes.

So, what do you see as intangible and inherent in human nature?

EES: The need to question! Humanity is a fretful consciousness that doesn’t adhere to the world like melted sugar in a cup of coffee: people question their presence in the world. Having a mind turns out to be a fundamental discomfort: we know that we’re fragile and that we’re mortal and alone. We ponder this life that is given to us and that will be taken away. The stamp of humanity is the ritualisation around death. No animal buries its dead. That existential alarm generates most of our behaviours, our beliefs, our customs, philosophies and our sciences and technologies. It has allowed us to dig the world and to build civilisations. In this hollow, humankind has taken his fill.

You also emphasise in this first volume and probably the next ones, the growing importance human beings give themselves in the world...

EES: Human growth is the other constant that History reveals. In this novel, Noam, the hero, is simply one among other natural beings; he doesn’t see himself as above them. That’s why I called this first book Paradise Lost. Humankind hadn’t yet turned itself into, as Descartes said, “master and possessor of nature”. Later, Noam wonders at the domestication of flora and fauna, at domination to the point of destruction.

Within these two constants, there are others, like love...

EES: Absolutely! Love is desire, the vital spark. Noam, my hero, is revealed to himself by a woman, Noura. Encountering other people, especially in the context of love, is one of the grand principles of individuation. Over the course of the volumes, Noam will hold on to his capacity for wonder.

Is Noam a part of you?

EES: I put a lot of myself into him. He is a lot like me, except that he has very long, very beautiful hair (laughs!). He has a talent for happiness, emotions, observation and deep-rooted love. Through this story and all its characters, I’ve expressed the tenderness I feel for certain beings. I don’t judge people. Neither does Noam. Evil is never seen as such: it’s the response to pain or humiliation.

Did the crisis we’re experiencing come into the design of this novel?

EES: Of course! The past is always viewed through the window of the present. There’s no other vantage point. I consider the past through the current destruction of the planet, for example. I discuss the Flood, which was a natural disaster independent of men, but now we’re the agent of annihilation. The impoverishment of the environment and global warming belong to contemporary anxiety. The loss of our autonomy is the other side of progress. We are interdependent and live in universes that are increasingly connected.

Do you think the catastrophes we’re in, including epidemics, will give us the impulse to change?

EES: I’m pretty Kantian. Kant said that humanity only improves by virtue of catastrophes. Evil is necessary for humans to produce what is good. Optimisation is always a reaction. We do better not because it’s good but because things are so bad they have to change! An example would be international regulatory authorities. I believe that humanity makes progress on the back of bad things. That’s what makes History accelerate. I’m an optimist out of pessimism.

But you’re still very optimistic: here you are at 60 launching into a project that’ll take decades!

EES: Yes. I shuddered when I started out, but I told myself, “Whatever happens to you, you’re giving yourself ten years of life! You won’t be able to be ill, you won’t be able to falter.” I am espousing momentum.

You’re talking about strength of mind...

EES: Exactly! Desire keeps us going. When a person is gripped by a desire, when you’ve got a reason to get up in the morning, when you agree to be tired because you know why and you’re happy to be, you’re embracing life! Tackling this project makes me feel a lot less old. I’m where I need to be, where I wanted to be. These moments of matching up to yourself are very powerful. I had to be ever so slightly crazed to embark, but once I’d begun, I realised that the whole novel was there and I just had to sit down for it to emerge. I’ve got thousands of pages in my head.

Does this project help you to be more yourself?

EES: That’s right. There’s a huge sense of fulfilment in the thought that you’re doing what you’re here for. You know, I’ve always flirted with the Encyclopaedia. I did my doctoral thesis on Diderot, someone who was passionate about the Encyclopaedia, who was as interested in technology as he was in spirituality. He was like a mentor for me. I realise that the periods where I went off in other directions expressed the same impulse and led to this project.

A way of fulfilling your calling in life...

EES: Every person wonders about what’s constructed in her and what’s revealed to her. On my way, there are choices that reveal construction – studies, a career – but there are also revelations. As we move forward, we discover what we are for, just us: we find out what we can contribute that no one else would. I think, as Marguerite Yourcenar wrote, that we don’t change: we become more profound. Become what you are, once you’re aware of it. And become really good at it. That’s how to find peace with yourself.

Isn’t that a bit megalomanic?

EES: You need to distinguish between ambition, which is a form of humility – surpassing yourself – and megalomania, which is the conviction that you’re superior. Confusing them is pretty serious. I’m someone who’s riddled with doubt, I’m always ready with admiration and I’m definitely not megalomanic.

Where does this appetite come from?

EES: I see myself as curiosity on legs! As a child, I frightened my parents because I used to take objects apart to know how they worked. Then it was the same with music, then philosophy... I continually quivered with a passion to understand! I want to enjoy things, but I enjoy them even more if I understand. I’m made of curiosity and desire.

It’s the same thing!

EES: Yes. And curiosity constitutes the first manifestation of tolerance.

What would you say to all those people who are anxious and depressed at the moment, in particular, young people who are in despair?

EES: Life is a journey that lets you find your place among other people and be yourself. Sometimes, circumstances conspire to delay or inhibit that project, but the project remains. You’ve got to seek it out, not forget about it and cultivate it. Let’s sieve our days and pick out what gives us strength, what seems essential to us and what heightens our vital spark. Is society atomising and dispersing us? Then, let’s dream! Dreaming brings us back to ourselves. It’s not easy, living, but what an adventure! Lockdowns and restrictions will come to an end.

Christilla Pellé-Douël

Fémi—9 - « A wonderful literary project. »

With La Traversée des temps (Crossing Time), Eric-Emmanuel Schmitt has finally published the first volume in the saga entitled Paradis perdus (Paradise Lost), the idea for which has been maturing in his mind for 30 years. His ambition? To tell the evolution of humanity from the Neolithic to our own time in eight novels through the eyes of an immortal character.

We meet a writer devoted to his art who takes us behind the wings of this wonderful literary project.

Fémi 9: What was the spark that ignited this project?

Eric-Emmanuel Schmitt: I think it was reading two authors I adore: Marguerite Yourcenar and Mika Waltari. They made me see the power of the historical novel, which makes it possible to reconstruct vanished ages and bring them back to life. The historical novel restores to us the flesh, blood, energy, smells and colours of a time and allows us to collapse the centuries. I was very taken by this capacity in fiction, and an idea came to me for an immortal hero who would tell the story of humanity by way of the technological, cultural, spiritual, philosophical and scientific developments of the major periods he lives through.

Fémi 9: Your hero is called Noam. Does the fact of having chosen a male protagonist mean you have a specific vision of immortality?

Eric-Emmanuel Schmitt: Yes, because men and women don’t approach it in the same way. I’ll develop this concept in the next novels with the appearance on stage of an immortal heroine enabling me to show that their relationship with time is different, if only in the way it affects their bodies. For women, the relationship to time is monthly, it’s linked to the fact that they are life-givers. But men don’t notice time and the ills of the body until they fall ill. I was touched by Noam as an immortal being because I don’t see immortality as a gift, I think it’s more of a burden, a sentence to perpetuity during which you go over and over the same questions and drag with you the same sorrows. I immediately heard the music of Noam’s soul and even if my role as an author is not to judge but to show human complexity, I loved him from the start: he’s kindly and open- minded with few certainties and those he has, he’s not afraid to question.

Fémi 9: You’ve been working on this literary project for 30 years. What stopped you bringing it to fruition earlier?

Eric-Emmanuel Schmitt: The whole concept involved a novel of 5,000 pages in eight volumes, so I needed a solid architecture to structure the book. Firstly, there was the intellectual work of digesting accumulated encyclopaedic knowledge, then I had to divide up History and present it in the grand epochs of change, revolution and transformation, which Noam will experience over 8,000 years. Then, there was the reflective work of the novelist so I could draw the dramatic thread of the story through several volumes. Those two challenges involve a constant balancing act which I try to maintain: the tension between analysis and the creative process. So, when I announced to my publisher that I was ready to launch into the novel I’d been talking to him about for 30 years, he was delighted but he was also afraid that that balance between the academic and the novelist would let the novel down. However, because I’d taken years to assimilate the historical culture I acquired, I’d been able to transform it into a more-or-less natural underpinning I could rely on, so now I could concentrate on the creative side during the writing phase.

Fémi 9: How do you steer such a project and continue to believe it’ll see the light of day when you’ve had it maturing for 30 years?

Eric-Emmanuel Schmitt: I confess I sometimes lost hope. I used to think: “Right, let’s go: this time you’re going to start writing.” I thought I was going to several times but each time, I found I still wasn’t ready. Because the project wasn’t ready, because I hadn’t solved analytically all the problems it threw up. So, I was cross with myself for a while. I saw myself as a failure and felt I was just procrastinating... But I think this novel was actually bigger than me and I needed to mature myself. That’s also part of these ambitious projects: they make you climb steps and push back boundaries before you’re up to them. The book made demands, and as I write novels only when I’m ready, it was only three years ago that I was finally able to launch into this one.

Fémi 9: What was the trigger?

Eric-Emmanuel Schmitt: My mother’s death. She was an extraordinary woman and I had a great relationship with her. I think the little boy still somewhere in me who believed his mother to be immortal died alongside her and I told myself that there was not a second to be lost. I’ve always loved life intensely but if I had something to achieve, I had to do it now. But at the same time, all the intellectual issues this literary project raised were finally sorted. So, when I’d got over my grief, I reached for my pen and it all came out.

Fémi 9: The links between humans and Nature are very important in this first volume. Was it critical to put that basic relation centre-stage?

Eric-Emmanuel Schmitt: Yes. I think we’re living in a time that’s totally unique, because humans have realised that they’ve probably gone too far in their domination and exploitation of Nature. And, in this first novel, Noam also wonders about the journey that led people to change the landscape, exploit the land and use up its resources. I called this first volume “Paradise Lost” as a reference to the long-gone time when our ancestors, who were not that numerous, were evolving in the heart of a bounteous natural world with no feelings of superiority or the will to dominate it... until the period of Prehistory I start my saga with: then you get the invention of societies, nomadic hunter- gatherers who become sedentary. They start to work, divide up tasks, have more children and, above all, they invent the household, housewives and a patriarchal society.

Fémi 9: Are there any authors who inspired you for this eight-volume saga?

Eric-Emmanuel Schmitt: In terms of the encyclopaedia, Diderot, of course! The founder of the first encyclopaedia promoted knowledge without hierarchies and I share the idea that there’s no high-level and no low-level knowledge. Like him, I’m someone with boundless curiosity and enthusiasms.

And for the historical and coming-of-age aspects, Alexandre Dumas. I owe him a love of reading and literature: it was his masterpiece, The Three Musketeers, that turned me into a serious reader at the age of eight.

Fémi 9: What do you do so as not to lose energy and get bored when you finally take on a long-term project like this one?

Eric-Emmanuel Schmitt: It’s both a pleasure and a source of anxiety when you get up without knowing what you’re going to do. Feeling involved in this story that’s demanding to exist is as stimulating as it’s exhausting. That said, I have sometimes felt I’m a slave to my novel (laughter). But I decided years ago to be happy and to love all the tasks that made up a writer’s life: imagining and writing but also cutting, starting again and rereading over and over.

I work like a navvy but I don’t suffer for it. And as soon as I’d written the last line of Book I, I started the second, which I’m just finishing.

Fémi 9: What have been the first reactions of your readers to Paradise Lost?

Eric-Emmanuel Schmitt: Really amazing! I’ve never been so nervous about one of my novels, but I’ve never been so pleased with the outcome, either. Even though I realise there’s a lot of anticipation about the sequels and that all these positive reactions give me sleepless nights! Up to now, the pressure has always come from me and I was able to deal with that OK but now I’m having to accept external pressure.

Since the novel came out, people have been coming up to me on the street and saying: “But you’re out walking your dogs! Get back indoors to your writing!” Their enthusiasm is pretty weird, but it’s also very exciting.

Ciné-Télé Revue (Belgique) - « An unrivalled storyteller »

An unrivalled storyteller publishes Volume I of a colossal project to tell the history of humanity. It all begins with Noam, 8,000 years ago...

This book revisits history and the founding myths; it’s philosophical, ecological... How do you categorise it?

It’s a world novel. There’s a first level of reading for pure pleasure, which I call “alexandre-dumas-ism”, and concealed under it all are multiple layers of knowledge and points of reflection.

It’s also a very beautiful love story. Is love timeless?

It’s essential. Noam is revealed to himself through love. Noura allows him to confront his father, to find his place and to reinvent it. That’s how he becomes a person who’s different from the other members of his clan. Otherwise, he wouldn’t have lived his life. Encounters with other people trigger that in all of us. Noura is in several thousand women. She leads her life without revenge: she’s a pre-feminist feminist.

The story has echoes of our own time: climate change, migrations, survivalism... Are we nearing the end of Paradise, too?

There’ve been narratives about the end of the world since time immemorial. In the past, it was the work of the gods, of one God or of Nature. Today, human survival appears under threat as a result of people having thought they were superior to the rest of creation. Despite that observation, there is hope that humans will redeem themselves, but they will only do that on the back of disasters.

Your hero is immortal. Is that an asset?

Immortality is a trial because it involves radical solitude. That means the same questions never let you go. It means shlepping one’s sorrows about in perpetuity. In this novel, I ask readers to embrace their mortality, to accept it and to love it.

One of the main themes is the opposition of civilisation and barbarity. Is progress bad?

Our ancestors had a relationship with Nature which we’ve lost. They saw themselves as living beings among other equivalent living beings and they saw that the elements had a soul. We think that’s naïve but it’s extremely wise because it’s about humility. Humans began to believe that they were the only ones with a spirit and as a result, they took hold of the world as though it were an object that belonged to them. By getting into the skin of our ancestors, I’ve tried to show that there’s a lost paradise, which is a simple way of inhabiting a world of abundance.

Your project is set to run to eight books. What’s in Book 2?

It’s coming out in October. The backdrop is Mesopotamia at the time of the Tower of Babel in a world that’s just invented writing, cities and social classes, when reason is

tinged with magic.

ANTONELLA SORO

La Tribune de Genève ( Suisse) - « A bestseller that will last »

A Zen colossus of exquisite delicacy and debonair erudition, at 60, Eric-Emmanuel Schmitt crosses every literary genre in Paradis perdus (Paradise Lost). The novel launches his eight-part series, La Traversée des temps (Crossing Time), which sets out to recast the world. From Neolithic Hunters and Gatherers down to the Industrial Revolution(s) of the 19th century, its hero Noam, possessed of immortality, will traverse some 5,000 pages.

You’ve taken on a literary decathlon, haven’t you?

You’re right, I wanted to bring together my literary output: novels, plays, film scripts, and so on. But above all, I wanted to change centuries... and bodies. Immortality can only happen in fiction and no academy can alter that. When I’m involved in an adventure story, I make sure to keep only a loose grip on the reins: I walk on the crest of the paradox between knowledge and surprise.

Isn’t it always a question of the innate versus what’s acquired?

That question is central to my project: what is humanity? The product of nature -- i.e., the innate -- or the product of human beings -- that’s to say, what’s acquired? To my mind, natural things don’t have a history. An anthill is like an anthill 100,000 years ago. On the other hand, human thought has evolved. I wanted to track that manufacturing process from human to human.

But without falling into an abyss of documentation. Why was that?

Precisely because I wanted to sediment culture, hence all those years to ruminate! (Laughs.) I wanted a voice to talk to me, not to be thumbing through catalogue cards! I’m a terrible example of the academic confraternity! But there you are: the words I write have to grow organically.

Hence the free sentimental extrapolations, too?

I see the immortal Noam’s love-life as an exception which could be glorious and is going to be painful, because his condition sets him apart. The first volume merely scratches the surface of an awareness: he senses that he’s not ageing and that’s already unbearable, like an odious betrayal, an eternal flight. Look at when he sees his son growing old...

Is that your way of domesticating death?

Probably. Maybe with the ambition for wisdom that writers cultivate, namely, to convince my readers that, given the plague of immortality -- the curse of bearing the same sorrows and ignorance --, it’s better to embrace mortality with humility.

It’ll go on for centuries. You’re like Noam, aren’t you: always out of step?

Doesn’t desynchronisation characterise all love stories?

Is love the main point about being human?

For Noam, it’s revelatory, certainly. It’s the catalyst for his filial, tribal and sexual identity. Love wrests him from his ego but reveals him to himself at the same time.

Why don’t you talk about homosexuality?

Actually, I’ve saved that chapter for the next volume in Mesopotamia and later on, more broadly, when Noam discovers Ancient Greece. But, anyway, no spoilers...

How did you find a balance between the subjects?

It was important for me to talk about women right from the first volume. I believe profoundly that humanity set itself a trap by becoming sedentary. Our hunter-gatherer ancestors practised equality between the sexes. It was when they settled that communities assigned women the roles of maternity and housekeeping. My female hunters don’t live like prostitutes in a brothel but as free Amazons.

What’s your favourite period on this world building site?

As a Hellenist and a Latin scholar, I’ve always had one foot in Athens and one in Jerusalem. I surprised myself by the pleasure I derived from talking about Prelapsarian man out in the wind and the natural world. A whole awareness specific to the 21st century came to mind: the presentiment that humans were causing their own exclusion from this planet. It seemed obvious to counter that with our ancestors’ animist way of life and their refusal to make divisions between so-called “intelligent” living beings. The Neolithic way of life has been considered perfunctory and childish but I see it as holding true wisdom.

After me, the Flood!

Novelist, playwright, film maker... “and screen writer!”, exclaims Eric-Emmanuel Schmitt, who can add philosopher and theologian to that combination of talents. Crossing Time – Paradise Lost functions through a kind of alchemy. Schmitt appropriates humanity with ease, according to his method. And after him, the Flood! Or so it seems, when we see his hero Noam’s emotional life struck by J.-J. Annaud’s Quest for Fire or appeal to the Elves’ tragedy in Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings. The writer adds still more weight to his baggage with considerable metaphysical expertise tinged with his own mystical insights. From the Bible to Gilgamesh, Kant, Spinoza and others, his prowess certainly keeps his promise. For all eternity, never give up.

Cécile Lecoultre

Moustique (Belgique) - « Getting all readers into the labyrinth of History... »

Eric-Emmanuel Schmitt is a veritable writing machine. Novels, novellas, short stories, monographs, plays... He writes a lot and there’ll be no slacking off any time soon: Eric-Emmanuel Schmitt needs to keep going until 2027. At least. That’s the time limit on the colossal project he’s taken on. Its aim: to produce a grand series of eight novels on the subject of humanity.

Despite delays due to the pandemic, La Traversée des temps (Crossing Time) has now been inaugurated with Episode I, Paradis perdus (Paradise Lost). Episode II is still in progress. “It’s coming out in October,” says Schmitt, adding that he is begging his publisher to agree to a pattern of one per year. Regarding the enormity of the task (this first book weighs in at nearly 600 pages and that’s an average among the eight that are planned), the author of Oscar and the Lady in Pink is philosophical: “When you climb the Himalayas, you don’t look at the summit, you look at your feet,” he laughs.

Paradise Lost opens the saga and rolls out the red carpet before Noam, our guide for the subsequent events, a character endowed with immortality who will live through epochs and who bears a passing resemblance to his distant literary cousin, Fosca, Simone de Beauvoir’s hero in her 1946 novel All Men are Mortal. Born 8,000 years ago, Noam wakes up in our time in Beirut – “Lebanon is the theatre of world conflicts,” says Schmitt, who follows in the tradition of Yuval Noah Harari, bestselling author of Sapiens, the perfect exercise in popularisation or in how an academic manages to enthral readers with the history of the world.

Having awoken from his long sleep, Noam buys the papers and discovers the world we’re living in, a world which, in an effort at survival, is trying to repair the damage caused by its latest occupants. He then decides to commit to paper the scope of his previous lives: cue for the book we’re about to read. His story begins in a Neolithic lakeside village where Pannoam, Noam’s father, is the village chief and is raising his son to be his successor. Except that... except that nothing goes according to plan. Pannoam embodies the invention of politics, and with public affairs come affairs of the heart, which come between father and son.

How did you come up with the idea of this fictional fresco to tell the history of humanity?

ERIC-EMMANUEL SCHMITT: It was an idea I had when I was 25 and just starting out as a lecturer. I wanted to create an immortal character who would travel through time and tell us about the changes that have made the history of humanity. But, although I was capable of the concept at 25, I couldn’t bring it to fruition and the idea became a kind of life project. It guided my reading for decades and informed my work as a writer. I tried to broaden my world so that one day I could breathe life into this fresco.

The series consists of eight episodes which go from the Neolithic to industrial revolutions. How did you orchestrate the story? I spent years poring over a tree of possibilities, which rapidly became a forest of possibilities that was so complicated it gave me migraines! But as soon as I began writing, confidence came to my aid and my characters took on a life of their own and I agreed to change my plans. When I started out, I knew that Noam, the book’s hero, would wake up in our time and that he’d be struck by our era and need to explain it, and I had the idea of shuttling between present and past.

The book describes the origins of power and also the power struggles embodied in the conflict between father and son... Yes, like the Bible stories or the world’s founding tales, it’s a way of symbolising how conflicts are played out within families. The idea was to describe the tipping point when our ancestors went from a nomadic to a sedentary existence with the introduction of work

and ownership. My hero, Noam, hesitates when he’s confronted with this new world, he hesitates between the father who embodies the new organisation and his uncle who symbolises freedom in Nature.

The society we see represented in Noam’s village with his father as its chief shows the appearance of the patriarchal system. Is that something historians corroborate? Many Prehistorians think that there was a change in the status of women at the point when societies became sedentary. When men and women were hunter-gatherers, women limited the number of children they had. It was when people became sedentary that they started having more, with the appearance of the concept of the household, the assignment of women to the task of keeping the household and the start of male dominance. I tried to indicate this submission to the home by contrasting it with the cave- dwelling female hunters who could do what they liked with their bodies and who weren’t prostitutes but free women.

The story involves the Flood and the rising waters threatening the village. That seems to mirror our own contemporary concerns about climate change... People have worried that the end of the world was nigh since they stepped on to the planet. The end of the world is a story without end. I wanted to show how our ancestors’ fear was different from our own today. Our ancestors were afraid of the gods and of Nature; we’re afraid of people. When Noam wakes up in Beirut at the start of the novel, he sees the state of the planet and young people’s anxieties and he realises that people have become the master and destroyer of Nature.

To what extent were you influenced by Yuval Noah Harari’s Sapiens with its subtitle “A Brief History of Humanity”? It encouraged me. I read it with great enthusiasm. It’s a fantastic summary of a huge amount of research. And the book’s success reassured me. I realised I wasn’t the only one to get excited by the invention of humankind, because that’s what it’s about.

Paradise Lost also shows a desire to revisit the conventional fictional worlds of fantasy and adventure stories. You seem to want to get back to the childlike pleasures of reading... That’s exactly it! The older I get, the more I realise how formative my first reading of The Three Musketeers was. That’s what I took from Alexandre Dumas: the pleasure of telling stories that involve anticipation, dramatic reversals, surprise and so on. The whole point of my project is to get all readers, no matter who they are, to enter the labyrinth of History.

Sébastien Ministru.

Libération - « High-end fusion. »

At five hundred and sixty-three pages, this book is a good weight and that’s just the beginning. Eric- Emmanuel Schmitt’s overture to his 19th-century-style saga, La Traversée des temps (“Crossing Time”), comes with generic and melodramatic packaging. He has given Book I the Biblical title Paradis perdus (“Paradise Lost”). This whimsical adventure (he calls it his “crazy project”) will run to eight books in total, although it’s not as hairbrained as you might think because it is set up in an organised way, probably on the basis of a contract: one per year until 2028, which is pretty much the pace the former academic and successful playwright keeps up anyway. We already know where the next seven volumes will take us: Babel and Mesopotamia; Egypt of the Pharaohs; Ancient Greece; Rome and the birth of Christianity; Medieval Europe; the Renaissance and the discovery of the Americas, and modern revolutions. The idea of telling the history of humanity from its origins in the form of a novel came to Schmitt when he was 25; according to Wikipedia, he will be 61 this Sunday. “Like Yuval Noah Harari crossed with Alexandre Dumas,” boasts his publisher.

A Novel?

It goes without saying that, if you’re going to keep readers involved over the time and space anticipated, you need good characters, and love and conflict. The thread connecting the thousands of years in this massive fresco is carried by Noam, alias Noah, who is indeed the man of the Flood, which the author revisits in Book II. We start in the Neolithic in a lakeside village where Noam’s father, Pannoam, is the village chief. Relations between the main protagonists – the hero’s parents, his uncle exiled to the forest, a healer and his daughter Noura whom Noam falls head over heels in love with – explore the genres of Bildungsroman and tragedy sometimes with mythological undertones. The good father and village chief in fact mask a tyrant and a traitor. Expect suspense.

A journey?

How will Noam get us through time? We first come across him waking up in a cave in our own time after more than one hibernation season. So, he’s immortal, which puts us in mind of another, less ambitious novel about time travel by Simone de Beauvoir (All Men are Mortal) but with a philosophical dimension. Noam never dies: triple advantage – the hero will become familiar to the reader; he will witness the world’s progress, and he embodies a moral consciousness observing the planet’s deterioration. This also allows Schmitt to shuttle between Prehistory and the 21st century and to pepper the pages with learned footnotes, about, for instance, hygiene down the ages, Noam’s encounter with Herman Melville in New York, the genealogy of medicine, and so on.

Paradise?

From the outset, there’s a critique on humanity’s destruction of the planet: “What’s the good of coming back to such a universe?” Noam asks himself. “God is now shut out of the apocalypse, man is enough.” Noam was born into a society that lived at one with Nature. He extols to survivalists he meets in our own time the purity of men’s lives in Prehistory. Cue for the author to incorporate thriller elements with a “Knights of the Apocalypse Operation” that’s armed to the teeth. This is high-end fusion.

FRÉDÉRIQUE ROUSSEL

Blogs reviews