Masterclass

Trailers

Monsieur Ibrahim et les Fleurs du Coran

x (x)

x (x)

x (x)

x (x)

x (x)

x (x)

View all trailers

Summary

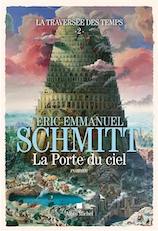

Paradis perdus (Paradise Lost) opened La Traversée des temps (Crossing time), a unique adventure story, with Heaven’s Gate as volume II.

Miraculously reappearing century after century, Eric-Emmanuel’s latest hero continues his journey down the river of time and sets off on a new search in the Ancient Near East. Noam is looking for his beloved who vanished in strange circumstances. Accompanied by his dog, he discovers a world in transformation, Mesopotamia, otherwise known as the Land of Fresh Water, where humans have just invented cities, writing and astronomy.

In the buzzing, vibrant city of Babel, glorious by both night and day, he comes up against the tyrant Nemrod, who resorts to slavery to build the highest tower ever conceived to act as Heaven’s gate and give access to the gods. Battling a revolving door of intrigues, treachery and pitfalls, Noam, the healer, finds himself in all manner of settings and meets characters of every kind. There’s Maël the child-poet, Gawan the mysterious Magician, Queen Kubaba mischievous and razor sharp, and Abraham Chief of the Hebrew Nomads, in denial of the new civilisation.

What will Noam choose to do? Will he sacrifice his deepest inclinations to devote his life to fight injustice?

In Heaven's Gate, with cheerful erudition, Eric-Emmanuel Schmitt dusts off an era madelegendary by the Bible. With the pen of a visionary and informed by the latest research in Assyriology, he reproduces the complexity and glories of Mesopotamia, a region we know so little about but to which we owe so much.

Reviews

Le Journal de Québec - « A monumental return to the past »

Continuing his grand saga, La Traversée du temps (Crossing Time), which tells the history of humanity, Eric-Emmanuel Schmitt invites readers to follow his hero, Noam, to the heart of Mesopotamia in La Porte du ciel (Heaven’s Gate). This thrilling, erudite, totally engrossing and superbly written novel traces the turbulent period of Babel 3000 years before Jesus Christ. Together with his lover, Noam learns about writing, astronomy and architecture.

Eric-Emmanuel Schmitt has produced a monumental return to the past, describing a rich civilisation that is nevertheless rarely explored in literature.

“I’ve been on a terrific journey!” he says enthusiastically in the interview. “I leapt into the third millennium before Christ in Mesopotamia. It was fantastic, because I was so far away but there were so many discoveries, so many wonders and surprises.”

“I was amazed at things that no longer amaze us, you know: life, writing, knowledge of the stars. Everything that we now see as completely obvious I was discovering with the astonishment of Noam. It was a great poetic refresher!”

No ordinary subject

Mesopotamia is no ordinary subject. “Mesopotamia, which is the oldest human civilisation, is a recent discovery. It was really only from the 1950s that archaeologists began properly to research and dig the soil of Iraq, finding thousands upon thousands of clay tablets that enabled them to reconstitute this first civilisation. It’s the oldest civilisation but knowledge of it is recent.”

He observes that novelists have not yet embraced it, although they’ve been embracing Egypt since the 18th century. “I was delighted to produce pretty much the first novel set in Mesopotamia, because when people talk about it, they talk about the end of Mesopotamia, Babylon when the Persians and Greeks were already invading it.”

Eric-Emmanuel Schmitt notes that, earlier, no one had the material and the knowledge to be able to talk accurately about the golden era of this civilisation.

Reading and dreaming

The period of research and writing was fascinating. “It involved both a lot of reading and also a lot of dreaming. I’ve always thought that dreaming – by which I mean ‘the imagination’ – was a way of exploring the world. I first got stuck into my research, and then I began to dream, generally making a big fire in the fireplace, sitting down in front of it and letting my ideas wander, hypnotised by the flames.”

His creative process worked perfectly. “My ideas suddenly took off with Mesopotamian sensations. It’s not enough just to know a lot: you’ve got to have sensations and images, you’ve got to feel the forces. Once you’ve got your intellect working, you’ve got to get your imagination working.”

A kind of trance? “Yes! It’s something I described in the first volume with Tibor, the healer, who said that, if you’re going to understand nature, you need to stare into rushing waters or the flames of a fire so as to become hypnotised and pass into a different state of awareness in order to notice the invisible links that go unnoticed. I am a great believer in the power of dreaming.”

His eternal brother

Noam, the saga’s hero, is a character who develops. For the writer, he has become a flesh-and-blood being. “It’s incredible, the place he occupies in my life. He’s my eternal brother. He has characteristics I feel very close to: curiosity, kindness and also sensuality. He is a man with passions.”

Eric-Emmanuel Schmitt affirms that he has many points in common with his character. “Noam has his own way of doing things, his obsession with Noura and his interest in medicine since he’s a healer, and he never stops moving forward. And then, all his questions about desire and feeling. I’m fully determined to follow him across several millennia.”

Next stop: Ancient Egypt

Marie-France Bornais

Le Figaro - « Dumas lives on! »

There are books whose sentences radiate the joy the author took in writing them. Eric-Emmanuel Schmitt’s La Porte du ciel (Heaven’s Gate) is one of those. Part II of his superb eight-part saga, which tells the story of nothing less than the history of humanity, runs to over 500 pages. It takes brio, erudition and imagination to build such a literary monument. Schmitt keeps you turning pages with madcap adventures and punchy dialogue. Let’s be clear from the outset: this sequel in a work without equal is breath-taking.

In Paradis perdus (Paradise Lost), we met the character of Noam recording his memoirs. Not those of a young man of 25, despite outward appearances, but of a man aged 8,000, because he was born in the Neolithic. With him, we experience intimate history (such as his love for Noura and power struggles) and then History with a capital H: the Flood, a fantastical rereading of the Bible. Now, in Heaven’s Gate, we leave the Prelapsarian age for the Babylonian centuries. Last seen, Noam had had his head split open in an act of thuggery. Yes, but from Volume I, we knew the man was immortal.

While he regains consciousness, beautiful Noura tells him what has happened since his “death”. She tells him of the terrible Derek she fled some decades ago and who has been looking for her ever since. Noura is worried: Derek mustn’t find them and still less see Noam because he would realise that he is invincible and his thirst for violence would be unquenchable. In brief, fear maketh the man.

Dumas lives on!

Far from the world, Noura and Noam are in love and want to start a family. But is that possible when they don’t belong to biological time? “Noura inhabited eternity as a woman, but eternity isn’t female.” Schmitt questions our human condition. Are we still alive if we cannot die? You’ve guessed it: the project won’t go as planned. Noura will disappear and Noam will go off in search of her. If time no longer exists, life will nevertheless go marching on.

In Schmitt’s fictional universe, history is a woman: Noura. Wherever Noam goes, he sees her, or at least, he fantasises about her. In the course of his search, he encounters writing, astronomy and cities, especially Babel, a monstrous settlement “rising like a mountain out of the ground” inhabited by a chaos of urchins and slaves. It is ruled by a tyrant called Nemrod, who keeps for himself the world’s most beautiful women. Might Noura be among them? In this universe, it pays to be canny, because there are spies everywhere. Who is the magician Gawan and what does Queen Kubaba, Nemrod’s rival, want?

Plots, treachery and deceit: this is a novel in which Dumas lives on! In it, Schmitt turns his hand to philosophy, history, metaphysics and story-telling. He rewrites the episode of the Tower of Babel, the sacrifice of Abraham, the epic of Gilgamesh. His review of the past strikes a chord with our contemporary world, whether critiquing people in power or mystics, those “ventriloquists” of God who’d like to rival the skies. Bring on Volume 3!

Alice Develey

La Dernière Heure (Belgique) - « You don’t read La Porte du ciel (Heaven’s Gate), you devour it! »

Eric-Emmanuel Schmitt continues his travels through time and discovers writing in the company of his hero, the immortal Noam.

You’ve got to be something of a magician (like Gawan) or full of good vibes (like Noam) to pull off such a tour de force: get readers passionately involved in the life of a man imbued with immortality who has survived the Flood and who, in this second volume of La Traversée des temps (Crossing Time) takes us by the hand and leads us to Mesopotamia just as the Tower of Babel is being built. Eric-Emmanuel Schmitt has the power to take us on this journey into the distant past, while building shrewd bridges between that world, so removed in time and space (3,500 years before Christ in what is now Iraq), and our own. You don’t read La Porte du ciel (Heaven’s Gate), you devour it! The proof? Schmitt’s readers are already asking when Volume 3 will be out.

“Noam is astonished at the cities he discovers, the new social order and human expansion,” he smiles. “I think things are about to get worse... He’ll start to change in the next volume, but he’ll still have a lot to discover. Noam will become a man who gets even more involved when he senses certain values coming under threat.” But let’s not get ahead of ourselves. For now, having lost his girlfriend and realised that he is immortal, Noam wanders into what was the cradle of humanity. A place where, today, all we see is a land of conflict, extremism and bloodshed. “What we start to see in this book is the scope of human ingenuity. It creates cities, which are both fascinating and repellent. There’s an element of terror that will continue to grow.”

Because, in Heaven’s Gate, the world is going through times of significant change. Not only are there cities, but there are also gods who enter people’s lives and change them fundamentally. “The city will show up social differentiations. For Abram, the world belongs to no one; people need to move about the world freely...” Themes that resonate poignantly in the 21st century.

In Heaven’s Gate Eric-Emmanuel Schmitt greedily indulges his erudition and his imagination. Writing is invented to change the face of the world. “Observing the irruption of writing into our lives with Noam’s naivety is kind of amazing. Because, initially, he thinks it’s a magic trick. But very quickly – and this is human ingenuity for you – writing is diverted from what it was invented for. Literature is born, and then, in the next book, hubris, which I call “the human bulge”. The idea that you can have your name carved in stone forever. Writing ushers in everything that’s human. It ushers in interest, ingenuity, dreams and the creation of the world. And man’s perpetual defiance of death. From now on, there will be esteem for writing and literature. This is just the beginning, because before, it wasn’t there.”

Planned in eight volumes (but don’t be surprised if there’s an extra one...), Crossing Time will speed up after the “slow periods”, as Eric-Emmanuel Schmitt explains. “That’s a feature of our history. The closer you get to our own time, the shorter the gaps between books, because there really are times when history accelerates,” says the author. In the 21st century, we’ve witnessed dramatic accelerations.

No more literary prizes for him

By becoming a member of the Goncourt Academy jury, Eric-Emmanuel Schmitt has, like his peers, agreed to forego the honour of winning one of France’s four biggest literary prizes, the Goncourt, the Prix Femina, the Médicis and the Renaudot.

“That’s it, I’ll never be nominated. From the moment I entered the Goncourt Academy, I knew that all the major literary prizes were over for me. Actually, that’s sometimes why it’s difficult to find new

jury members because they’re hoping to win the Goncourt (laughs). It’s a forfeit. And it’s forever. In the same way, a member of the Femina jury can’t win the Goncourt, etc. But you can win the smaller prizes or, like me, foreign prizes. So, if you’re happy with that, you’ve still got that possibility.” (Laughs.).

When Greta Thunberg and Eric Zemmour get together

Heaven’s Gate tells of the construction of the Tower of Babel, but, as in the first book, this one is punctuated by incursions into the present. Thus, we meet the character of Britta Thoresen, a young activist fighting for the planet. “When she talks, she gets asked: Who are you? as opposed to, What are you saying? That’s always been a way to diminish critics,” Eric-Emmanuel Schmitt observes. “Britta embodies the revolt and exasperation of a generation that’s going to experience the consequences of what their predecessors have done. For me, there’s no answer to that one.”

When you see what’s happening around Eric Zemmour today in France, you can see similarities: people see a personality without listening to what he says. “I don’t know if the people following him don’t hear what he says,” the writer qualifies. “The media don’t listen to what he says because it’s fun to have a new personality for the tabloids. On the other hand, I think that, unfortunately, the people who follow him and want to vote for him hear what he says perfectly well. And that’s what I find alarming, because it’s a discourse of division. His reading of the history of France is completely ridiculous. He’s an intelligent man but he peddles distorted knowledge to serve his ideas.”

Isabelle Monnart

Le Point - « The Poetics of Excess »

Eric-Emmanuel Schmitt loved Noam so much that he has given him eternal life. The hero of La Porte du ciel (Heaven’s Gate), born in the Neolithic, has received the gift (the curse?) of immortality. His life is the focus of a monumental literary project, whose ambition is to tell nothing less than the history of humanity from Prehistory to our own time in eight volumes. In Paradis perdus (Paradise Lost), the first in the grand saga that is La Traversée des temps (Crossing Time), Noam fell in love with the sublime Noura and experienced the Flood. Now he finds himself in the golden age of Mesopotamia, just when the Tower of Babel is being built under the command of the tyrant, Nemrod. To satisfy his dreams of architectural excess, Nemrod has reduced thousands of men and women to slavery. Could it be that Noura, who disappeared in the book’s opening pages, is one of the victims of this human trafficking? Maybe she has been shut up in the harem... To find her, Noam travels through the Land of Fresh Water, enters the service of a lustful queen outwardly wizened but with a razor-sharp mind (an awesome character!), cracks open skulls, disguises himself, merges with a bird, plucks out all the hairs on his body and cuts off a few fingers. “What did we know of the world? We had no notion of its size or shape. Knowing nothing, we used our imagination,” says Noam.

Like his hero, Eric-Emmanuel Schmitt exercises the workings of his creativity to lead the reader down the path of vanished eras. In so doing, he combines his outstanding erudition (he has been amassing the intellectual material required to recreate humanity’s earliest epochs for decades) with his irresistible urge to produce a thumping good read. He is serious and playful in equal measure, shifting seamlessly between farce and tragedy, folly and philosophy, scholarship and sex. The novel begins like the first, with Noam waking up at a time of calamity: our own. “By advancing from power to excess power in the name of progress, humanity has become a threat to itself,” Schmitt writes. A disarming feature of this ambitious project is that his aim is less to satisfy an ego through the arrogant construction of a literary Tower of Babel, but rather to preserve the world by celebrating each of its marvels – before they all collapse?

Élise Lépine

La Vie - « A thrilling adventure »

This is the second volume in Eric-Emmanuel’s monumental fictional history of humanity, which opened with Paradis perdus (Paradise Lost) and is set to run to eight books. We left the narrative at the time of the Flood. Now we are in the Land of Fresh Water, Mesopotamia, where men have just invented irrigation, the earliest cities and writing. “Telecommunications began with writing. Breath become petrified...” the author tells us. Noam (alias Noah, the man of the Flood), the saga’s hero, sets off in search of his lost love, Noura. His journey takes him to the gates of Babel, the city where the tyrant Nemrod wants to build a tower so high it will give him access to the gods and open the gates of Heaven. The thrilling adventure of Noam and his friends is footnoted by the author, who reveals his sources and authenticates the factual details without those asides getting in the reader’s way. At the start of every segment, the novelist conducts a parallel, contemporary inquiry where we find the immortal Noam confronting a group of terrorists determined to blow up the planet. It all functions seamlessly: the reader was caught up in a seminal, philosophical and Tolkienesque tale then finds himself in a thriller. Look to the past to explain the present. Eric-Emmanuel Schmitt’s extraordinary and joyful erudition transports the reader. We await Volume III...

Yves Viollier

Les Affiches d’Alsace et de Lorraine - « A unique adventure story »

Eric-Emmanuel Schmitt, member of the Goncourt Academy, playwright, novelist, writer of non- fiction and film director, whose work has been translated into 48 languages and performed in more than 50 countries, needs no introducing.

This winter, he is back with a new opus: Volume II of La Traversée des Temps (Crossing Time), promisingly titled La Porte du ciel (Heaven’s Gate).

Paradis perdus (Paradise Lost) opened Crossing Time, an adventure story like no other. Reappearing miraculously from century to century, Eric-Emmanuel’s latest hero continues his journey down the river of time and sets off on a new search in the Ancient Near East. Noam is looking for his beloved who vanished in strange circumstances. Accompanied by his dog, he discovers a world in transformation, Mesopotamia, otherwise known as the Land of Fresh Water, where humans have just invented cities, writing and astronomy. In the buzzing, vibrant city of Babel, glorious by both night and day, he comes up against the tyrant Nemrod, who resorts to slavery to build the highest tower ever conceived to act as Heaven’s gate and give access to the gods.

Bravely and skilfully, Schmitt takes readers into the maze of an era made legendary by the Bible.

Thanks to a detailed study of the era, he has recreated the décor and ambience to offer readers an unparalleled window on to the complexity and glories of Mesopotamia.

Thus, we follow a multitude of characters: Noam the healer, Maël the child-poet, Gawan the mysterious Magician, Queen Kubaba mischievous and razor-sharp, and Abraham Chief of the Hebrew Nomads, in denial of the new civilisation.

Noam must choose: will he be able to sacrifice his deepest inclinations to devote his life to fight injustice?

A stupendous saga, Heaven’s Gate is also a way into another world, so far from yet so near our own. “I began to keep company with a tree, a massive pine that kept its fellows at a respectable distance by rising high above them. At its base, its vast trunk sprouted only a few branches, as if making itself inaccessible, then it rose into a thin shaft, up into the clouds, where it put out more boughs, so high that I could not make out the crown. I was struck by the power of that pine tree. Even with my back to it, I could feel its presence, calling to me, insisting, and I turned round: the tree was demanding that I join it, stroke it, embrace it and lie down at its foot. There on a soft bed of rotting needles, I felt wide awake, tingling and transfixed. Whenever I felt the urge to leave, it commanded me to stay. It held me in its snare. Hunger alone, gnawing at my belly, wrested me from its clasp.

I don’t know the exact influence it was exerting when an incident informed me.”

Geneviève Senger

Le Soleil - « A fresh look at Mesopotamia »

Eric-Emmanuel Schmitt returns to readers with La Porte du ciel (Heaven’s Gate), the second volume in La Traversée des temps (Crossing Time), his saga that revisits the history of humanity. Still enveloped in the story of the immortal Noam, readers now leave the Neolithic to focus on the civilisation of Mesopotamia, a rich and all-but-forgotten population to whom today’s men and women owe their earliest major developments but, equally, some of their failings.

Does the word “Mesopotamia” suggest something rather vague to you? Is it perhaps associated with a distant and half-remembered history lesson? If so, don’t feel bad about it, says Eric-Emmanuel Schmitt in his interview with Le Soleil.

Most of what we know about this Prehistoric civilisation is actually “pretty recent”, observes the Franco-Belgian writer. Research dates mainly from the early 1950s. It was only really then that historians began to look seriously at the culture and daily life of this Middle Eastern people settled between the Tigris and the Euphrates. Today, we would situate them on the territory of Iraq.

Although Schmitt doesn’t go so far as to say that literature has deliberately avoided Mesopotamia, he admits that writers most certainly didn’t know about it.

“Even the people who wrote the Bible talk about “Egyptians” when they don’t know, although they’re often talking about Mesopotamians. [...] The civilisation was dead, you know, when people began to talk about it. There was a kind of substitution effect. [...] I think that’s how fiction hasn’t had time to embrace the period,” explains the Goncourt Academy member.

Although, in creating Heaven’s Gate, Schmitt conducted a good deal of research into the period and the people who lived in the region, he also wanted to let loose his writer’s “dreams”, keen to add flesh to the historical facts, the bare bones as it were, of his work.

“The landscapes and characters suddenly take shape through the schematic information I receive. At that point, another part of my brain is at work. And, I have to admit, that’s more important for a novelist,” he laughs.

He thus had a lot of fun putting words to the settings and situations that belong to Mesopotamia. Noam, for example, arrives in the city of Babel and encounters the tyrant Nemrod who wants to build a vast tower that will reach the sky: the Tower of Babel. He will also witness the construction of the earliest cities and thus the first frontiers between the urban world and the country.

Mastering history

Beyond the pleasure of writing and imagining these vanished times, Eric-Emmanuel Schmitt also wanted to shed light on a section of the past in which European and American populations still have their roots.

“It was a time when humanity leapt forward and ushered in an era humankind was never going to leave. [...] Human beings entered a phase that continues to define us to this day, and today we no longer question it,” he deplores, recalling that it saw the emergence of major technologies, like writing, astronomy and the “domestication” of water and fields.

But it was also when less admirable concepts were spawned: the invention of slavery and the division of social classes.

The key point about Crossing Time is to “view the present through eyes of the past”, and it’s no accident that the central character in the saga is amazed at the progress of civilisation. For Schmitt,

it is important to know history and never to stop questioning it, in terms of the societies we live in and contribute to.

“[...] We should question the division of the role of men and women, what it means to live in a city, and so on: we shouldn’t take those things for granted. Humans invented them at a certain point in history,” adds this novelist-playwright.

He sees Noam as taking on the role of a “brother” for readers, someone who’s neither a monster nor a hero. Modest and above all curious, his protagonist becomes a witness who guides readers through the many philosophical passages incorporated into the novel.

A love story

Crossing Time is a historical and philosophical saga, but for Schmitt it is also a love story between Noam and Noura.

While the young man becomes himself when he meets Noura in Paradis perdus (Paradise Lost), in Heaven’s Gate, Noura also makes him experience the pain of a relationship.

Does that mean love is intrinsic to the history of humanity?

“You know, when you tell stories about the past, you tell the variations and the constants. That’s to say, you tell the story of history and anthropology. For me, it’s human nature to need to receive and to give love. For me, it’s part of the very definition of humankind. Thereafter, the context in which that’s expressed is variable,” says the writer, who, in his next volume, will take readers to the heart of Ancient Egypt.

Eric-Emmanuel Schmitt declares that he is not sorry to have embarked on the project, immense though the undertaking is. Although he admits to being “shattered” at the end of every day and feeling as though he’s given everything he’s got, he also says that he gets up every morning with the certainty that he wants to go on creating the next novels. Literature is where he gets his energy, he affirms.

“I’m permanently afraid, but I never wish I weren’t writing!” he concludes, with a smile in his voice.

Léa Harvey